|

A

Tribute to Ollie Johnston

The Disney

Company on Ollie Johnston

April 15, 2023 11:00 pm

Ollie Johnston, one of the greatest animators/directing animators in

animation history and the last surviving member of Walt

Disney’s

elite group of animation pioneers known affectionately as the

“Nine Old Men,” passed away from natural causes at

a long

term care facility in Sequim, Washington on Monday April 14th. He was

95 years old. During his stellar 43-year career at The Walt Disney

Studios, he contributed inspired animation and direction to such

classic films as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,”

“Pinocchio,” “Fantasia,”

“Song of the

South,” “Cinderella,” “Alice in

Wonderland,” “Peter Pan,” “Lady

and the

Tramp,” “Sleeping Beauty,”

“Sword in the

Stone,” “Mary Poppins,” “The

Jungle

Book,” “Robin Hood,” “The

Rescuers,” and

“The Fox and the Hound.”

In addition

to his achievements as an animator and

directing animator, Johnston (in collaboration with his lifelong friend

and colleague Frank Thomas) authored four landmark books: Disney

Animation: The Illusion of Life, Too Funny for Words, Bambi: The Story

and the Film, and The Disney Villain. Johnston and Thomas were also the

title subjects of a heartfelt 1995 feature-length documentary entitled

“Frank and Ollie,” written and directed by

Frank’s

son, Theodore (Ted) Thomas. In November 2005, Johnston became the first

animator to be honored with the National Medal of Arts at a White House

ceremony.

Behind every

great animated character is a great

animator and in the case of some of Disney’s best-loved

creations, it was Johnston who served as the actor with the pencil.

Some examples include Thumper’s riotous recitation (in

“Bambi”) about “eating greens”

or

Pinocchio’s nose growing as he lies to the Blue Fairy, and

the

musical antics of Mowgli and Baloo as they sang “The Bear

Necessities” in “The Jungle Book.”

Johnston had his

hand in all of these and worked on such other favorites as Brer Rabbit,

Mr. Smee, the fairies in “Sleeping Beauty,” the

centaurettes in “Fantasia,” Prince John and Sir

Hiss

(”Robin Hood”), Orville the albatross

(”The

“Rescuers”), and more than a few of the

“101

Dalmatians.”

Roy E.

Disney, director emeritus and consultant

for The Walt Disney Company, said, “Ollie was part of an

amazing

generation of artists, one of the real pioneers of our art, one of the

major participants in the blossoming of animation into the art form we

know today. One of Ollie’s strongest beliefs was that his

characters should think first, then act…and they all did. He

brought warmth and wit and sly humor and a wonderful gentleness to

every character he animated. He brought all those same qualities to his

life, and to all of our lives who knew him. We will miss him greatly,

but we were all enormously enriched by him.”

John

Lasseter, chief creative officer for Walt

Disney and Pixar Animation Studios and a longtime friend to Johnston,

added, “Ollie had such a huge heart and it came through in

all of

his animation, which is why his work is some of the best ever done.

Aside from being one of the greatest animators of all time, he and

Frank (Thomas) were so incredibly giving and spent so much time

creating the bible of animation - ‘Disney

Animation: The

Illusion of Life’ - which has had such a huge

impact on so

many animators over the years. Ollie was a great teacher and mentor to

all of us. His door at the Studio was always open to young animators,

and I can’t imagine what animation would be like today

without

him passing on all of the knowledge and principles that the

‘nine

old men’ and Walt Disney developed. He taught me to always be

aware of what a character is thinking, and we continue to make sure

that every character we create at Pixar and Disney has a thought

process and emotion that makes them come alive.”

Glen Keane,

one of Disney’s top supervising

animators and director of the upcoming feature

“Rapunzel,”

observed, “Ollie Johnston was the kind of teacher who made

you

believe in yourself through his genuine encouragement and patient

guidance. He carried the torch of Disney animation and passed it on to

another generation. May his torch continue to be passed on for

generations to come.”

Andreas Deja,

another of today’s most

acclaimed and influential animators paid tribute to his friend and

mentor in this way, “I always thought that Ollie Johnston so

immersed himself into the characters he animated, that whenever you

watched Bambi, Pinocchio, Smee or Rufus the cat, you saw Ollie on the

screen. His kind and humorous personality came through in every scene

he animated. I will never forget my many stimulating conversations with

him over the years, his words of wisdom and encouragement.

‘Don’t animate drawings, animate

feelings,’ he would

say. What fantastic and important advice! He was one of the most

influential artists of the 20th century, and it was an honor and joy to

have known him.”

John

Canemaker, Academy Award®-winning

animator/director, and author of the book, Walt Disney’s Nine

Old

Men & The Art of Animation, noted, “”Ollie

Johnston

believed in the emotional power of having ‘two pencil

drawings

touch each other.’ His drawings had a big emotional impact on

audiences, that’s for sure — when Mowgli and Baloo

hug in

‘The Jungle Book;’ when Pongo gives his mate

Perdita a

comforting lick in ‘101 Dalmatians;’ when an

elderly cat

rubs against an orphan girl in ‘The Rescuers’

— Ollie

Johnston, one of the greatest animators who ever lived, deeply touched

our hearts.”

Born in Palo

Alto, California on October 31, 1912,

Johnston attended grammar school at the Stanford University campus

where his father taught as a professor of the romance languages. His

artistic abilities became increasingly evident while attending Palo

Alto High School and later as an art major at Stanford University.

During his

senior year in college, Johnston came

to Los Angeles to study under Pruett Carter at the Chouinard Art

Institute. It was during this time that he was approached by Disney

and, after only one week of training, joined the fledgling studio in

1935. The young artist immediately became captivated by the Disney

spirit and discovered that he could uniquely express himself through

this new art form.

At Disney,

Johnston’s first assignment was

as an in-betweener on the cartoon short “Mickey’s

Garden.” The following year, he was promoted to apprentice

animator, where he worked under Fred Moore on such cartoon shorts as

“Pluto’s Judgment Day” and

“Mickey’s

Rival.”

Johnston got

his first crack at animating on a

feature film with “Snow White and the Seven

Dwarfs.”

Following that, he worked on “Pinocchio” and

virtually

every one of Disney’s animated classics that followed. One of

his

proudest accomplishments was on the 1942 feature

“Bambi,”

which pushed the art form to new heights in portraying animal realism.

Johnston was one of four supervising animators to work on that film.

For his next

feature assignment, “Song of

the South” (1946), Johnston became a directing animator and

served in that capacity on nearly every film that followed. After

completing some early animation and character development on

“The

Fox and the Hound,” the veteran animator officially retired

in

January 1978, to devote full time to writing, lecturing and consulting.

His first

book, Disney Animation: The Illusion of

Life, written with Frank Thomas, was published in 1981 and ranks as the

definitive tome on the Disney approach to entertainment and animation.

In 1987, his second book, Too Funny For Words, was published and

offered additional insights into the studio’s unique style of

visual humor. A detailed visual and anecdotal account of the making of

“Bambi,” Walt Disney’s

“Bambi”: The Story

and the Film, the third collaboration for Thomas and Johnston, was

published in 1990. The Disney Villains, a fascinating inside look at

the characters audiences love to hate, was written by the duo in 1993.

In addition

to being one of the foremost animators

in Disney history, Johnston was also considered one of the

world’s leading train enthusiasts. The backyard of his home

in

Flintridge, California, boasted one of the finest hand-built miniature

railroads. Even more impressive was the full-size antique locomotive he

ran for many years at his former vacation home in Julian, near San

Diego. Johnston had a final opportunity to ride his train at a special

ceremony held in his honor at Disneyland in May 2005.

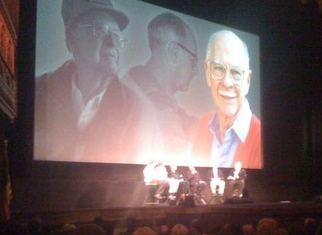

The

pioneering animator was honored by the Studio

in 1989 with a Disney Legends Award. In 2003, the Academy of Motion

Pictures Arts and Sciences held a special tribute to him (and Frank

Thomas), “Frank and Ollie: Drawn Together,” in

Beverly

Hills.

Johnston and

Thomas were lovingly caricatured, and

even provided the voices, in two animated features directed by Brad

Bird, “The Iron Giant,” and

Disney/Pixar’s “The

Incredibles.”

Johnston

moved from his California residence to a

care facility in Sequim, Washington in March 2006 to be near his

family. He is survived by his two sons: Ken Johnston and his wife

Carolyn, and Rick Johnston and his wife Teya Priest Johnston. His

beloved wife of 63 years, Marie, passed away in May 2005. Funeral plans

will be private. In lieu of flowers, the family suggests donations can

be made to CalArts (calarts.com), the World Wildlife Fund

(worldwildlife.org), or National Resources Defense Council (nrdc.org).

The Studio is planning a life celebration with details to be announced

shortly.

|